When I made the bittersweet decision to leave my job as a bookseller at the Barnes & Noble in Medford, Oregon, after having worked there for over seven years, there were three primary factors that kept me holding on a little longer: (1) I worked with some genuinely wonderful people whose friendships I value; (2) there’s really just something great about working in a big bookstore; and (3) my Horror section.

I started at Barnes & Noble as a seasonal worker in December of 2016. I was twenty-one years old, which is strange both to realize and to write out in this sentence, because it doesn’t necessarily feel like a long time ago, but it also feels like a different life. This May, I’ll be turning twenty-nine, and the early-twenties version of me seems like an entirely different person.

There’s a lot I could say about my experience at Barnes & Noble, how it helped me as a writer, how it helped shape me as a person, the positives of the bookstore experience contrasted with the negatives of the corporate bookstore experience, plus the many meaningful connections I made with people, and maybe I will write about those things sometime. But what I want to write about here is the creation of the Horror section at my store, and how my love of the horror genre was, for a long time, tied to that section.

Back then, when I first started at B&N and for the next few years, there was no official section for horror. This was true not just of my store, but of the company at large. No official horror sections. Established horror writers could be found anywhere among Fiction, Mystery/Thriller, Sci-Fi, or Fantasy. It wasn’t long after being hired as an employee, not merely as a seasonal worker, that my managers apparently saw the potential in my love of the horror genre. If I’m recalling correctly, it started as a single bay; no more than five or six shelves loosely stocked with a few obvious authors, Stephen King making up the majority. I got to set up the section, move the books, make sure all was neat and pretty. Not long after, I was encouraged to essentially “go crazy” shortlisting new titles into the store to fill up the shelves. This was when the real work of building and curating the horror section began. I didn’t realize at the time how this process would expand my own horizons as a lover of the genre.

Now, I had always gravitated towards dark and spooky things. Don’t know what to blame for that, though. Could be how some of my clearest and earliest memories are of nightmares, with images that I still remember along with the feelings they gave the little-child-version of me, feelings of fear so deep, I hesitated to share them with the adults around me. What if I scared them by sharing these things? I thought. I could blame my being introduced possibly a little too early to certain films, like Hitchcock’s The Birds somewhere around age eight or nine. I could blame the bizarre era of surreal children’s cartoon shows that I grew up in, an era populated by children’s stories that mingled ridiculous, over-the-top humor and wackiness, with characters, narratives, and themes rooted in the mystic, the paranormal, the monstrous, and even the uncanny (which paired nicely with Disney’s final era of hand-drawn animation, these last films being surprisingly mature and dark and even disturbing).

All that to say: my taste in fiction was primed toward the Weird early on, and I discovered Stephen King at age 13-14. From consuming most of King’s published work, to discovering Peter Straub, then expanding to a number of authors that also proved important and formative to me as a writer and a person—such as Richard Matheson, Dan Simmons, William Peter Blatty, Shirley Jackson—my mid to late teen years made a horror lover out of me. Being put in charge of building and curating the horror section for the bookstore where I worked in my early twenties put me unknowingly in a unique position to grow alongside the selection of books. It was a joy and an honor.

When my section was expanded to two bays, I gave myself the direct goal of diversifying it. As it stood, the main names were mostly obvious: Stephen King, Edgar Allan Poe, H. P. Lovecraft, Clive Barker, V. C. Andrews, Dean Koontz, plus a couple titles from Richard Matheson, Shirley Jackson, and Dan Simmons.

What I wanted was for this part of the store to become a haven of the genre, representative of its wideness and diversity. I spent time researching women horror authors, horror authors from different backgrounds, cultures, etc, and classics we for some reason didn’t already carry. With no books officially labeled horror, this also meant discovering a few authors who were already in the store but lacking the perfect home. In this way, a new variety came not merely to the shelves, but to my life, with such authors (or editors) as Tananarive Due, Gemma Files, Carmen Maria Machado, Ania Ahlborn, Lauren Beukes, Paul Tremblay, Dathan Auerbach, Poppy Z. Brite, Ramsey Campbell, Ellen Datlow, Nicole Cushing, Sheridan Le Fanu, Robert Chambers, Arthur Machen, and Kathe Koja. I became familiar with names that would later mean a great deal to me as a lover of the genre, once I’d finally read their books, like Stephen Graham Jones, or Victor Lavalle.

Although I’m not entirely certain of the exact time, Barnes & Noble as a company did eventually bring back the Horror section. If I were to estimate, I’d say that happened in 2020. But in those early years, after shelving incoming new titles to my section, then straightening it up to make it look pretty, I’d step back and feel proud. A special few customers relished in the growing selection; it was, I hope, as much a haven for them as it was for me. I kept such close watch over the section that, when I came in to work after a couple days off, I could often tell, by sight alone, what titles had sold, and so I did the stocking and restocking on my own, with the support of my manager who did her best to make sure my shortlists were always approved.

There was a brief period, too—which I look back at with a slight mixture of longing and regret—when virtually any shortlist would go through. This was before I discovered the wider world of Indie Horror, which is to say: I didn’t realize how much power I had back then that I could’ve been taking advantage of. I ordered in titles from Gemma Files, Stephen Graham Jones, John Ajvide Lindqvist, Adam Nevill, Koji Suzuki, Clay Chapman, Todd Keisling, J. F. Dubeau, Aliya Whiteley, and so many more, not realizing how, one day, some of those same titles wouldn’t be approved to come into stores anymore, at least not with such ease. I’ll get to that. At the time, though, it was like my little horror section’s golden age before the company’s big changes. There was a unique thrill to discovering the name of a new author, or even the name of a reputable small press, and going down lists of titles and shortlisting a number of them for my section.

Then came the company making horror sections official, at last. My horror section became a standalone space with four whole bays. It became self-sustaining (a most wonderful Frankenstein’s monster), but I didn’t let this lessen my passion for curating it and seeking out new titles and new authors to bring in. However, changes in the company also meant tighter restrictions on what could be ordered into stores.

With the support of my manager, I was able to bring in obscurer titles every now and then, but with less frequency and less flexibility. It was during this period that I made seismic discoveries in my world as a reader and writer of horror: John Langan, Mariana Enriquez, Thomas Ligotti, Laird Barron, Brian Evenson. I set up enduring displays dedicated to Weird or Cosmic horror, displays which gained small followings in loyal and excited customers. I believe I still remember a number of authors—or more titles from authors we may have had only a couple titles for—I was able to bring in for one of the last bigger shortlist orders, months ago: Michael Wehunt, Eric LaRocca, S. P. Miskowski, Mike Salt, Cynthia Pelayo, Ronald Malfi, Scott R. Jones, Gus Moreno, Livia Llewellyn, Jac Jemc, Andrew Najberg, MJ Mars, Scott J. Moses, Shaun Hamill, Craig DiLouie, Robert Levy, Timothy Hobbs, Andrew Sullivan, John Hornor Jacobs, V. Castro, Premee Mohamed, Scott Thomas, Daniel Braum, Noah Broyles, and many, many more. This was in addition to exciting works already coming in from authors like Christopher Golden, Gabino Iglesias, Nick Medina, Philip Fracassi, Gwendolyn Kiste, Richard Chizmar, Shane Hawk, et al. I absolutely cannot and would not take credit for these and other writers being in the section, rather it was simply my honor to either bring them into the store, or to have them already in the section and to shelve and display them.

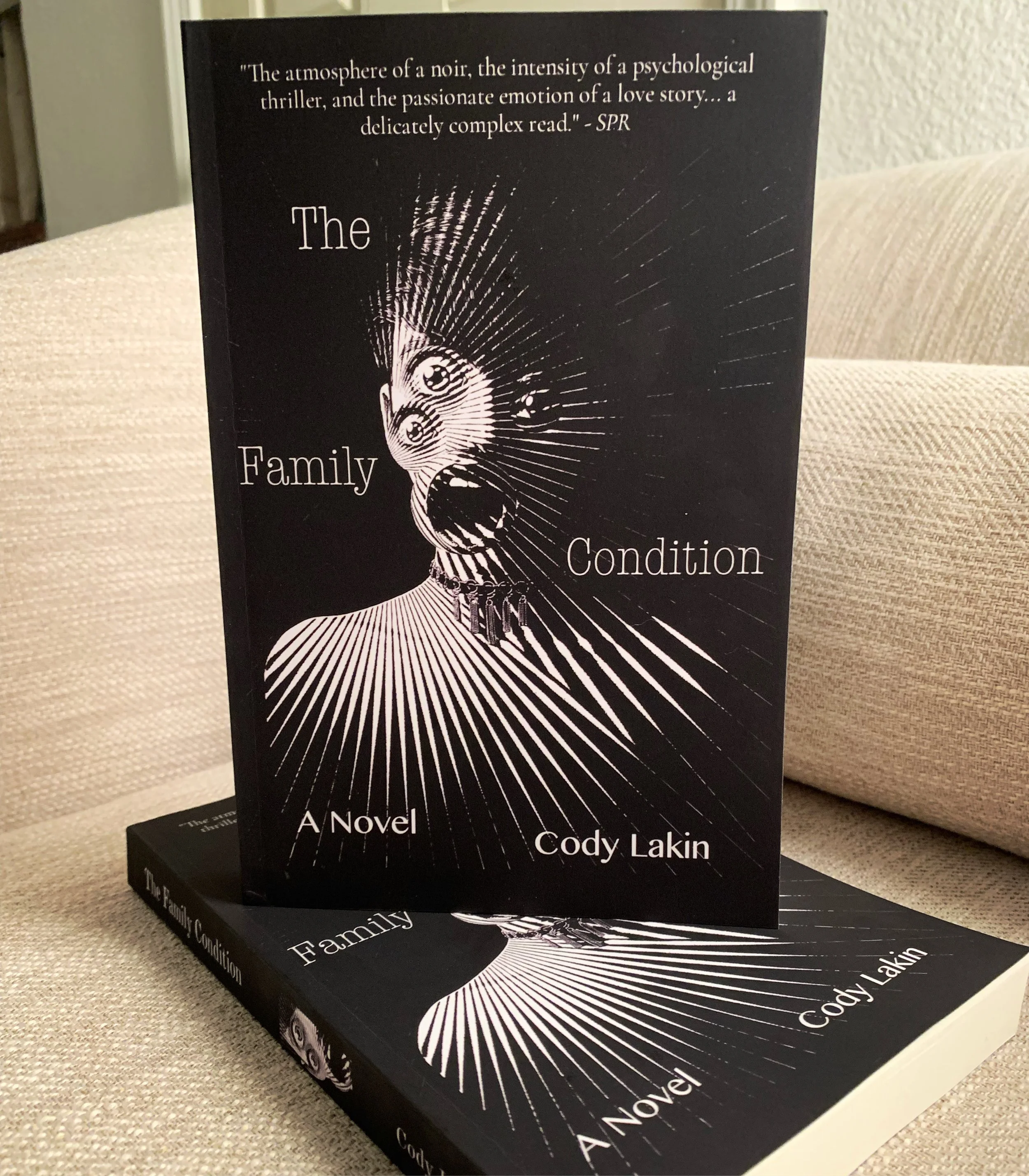

In 2022, my book The Family Condition was released. I’ll never forget the running start given to me by the store I worked in, how I probably shortlisted ten or so titles of my own book and was so excited to see it on the shelf in my own horror section. My manager, however, ordered fifty copies in. I’ll never forget that—a box filled with my book, with a face-out in the section. When those fifty copies sold, I didn’t put in an order, my manager again did, this time for a hundred. Later, of course, Barnes & Noble would approve The Family Condition for distribution company-wide, but it got a head start in my store. I recount this with inexpressible gratitude to the wonderful people I worked with.

Toward the end of my time as the Horror Expert at that store, my frustrations with the ordering process had become considerable. From a business standpoint, sure, it makes sense… but we were told, once, that individual stores would be given a lot of power to curate and personalize their selections. You’ve probably even read articles about Barnes & Noble modeling itself after indie bookstores, doing away with the corporate model of every store having the same selection. I was excited about that, but I never saw it become a reality. My experience was the opposite. By 2023, with a lot of experience working with customers as a bookseller and a curator of more than one section, I felt like the company was saying to me, “We’re giving you the choice of what to bring into your store! But it’s multiple choice and there’s only two—sometimes three—options!” Even established classics became strangely difficult to get approved for shortlists. I never imagined having to fight for work from Arthur Machen, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Chambers, Jane Webb, William Hope Hodgson, etc, but at times we did. Close coworkers of mine met the same struggles in their own sections, like poetry, sci-fi, and fantasy.

In the last couple years, I could often be caught saying, “My horror section is a good one, but it’s at about 70% of its potential power.” If I were given complete and total control over a horror section, I like to think it’d be a spectacle. Maybe not the smartest section in terms of, you know, money, but when it comes to a great selection in art, the main factor can’t always be profit. I learned that during my time at the independent and stunningly eclectic movie rental store called Couch Critics, which was my first job back in Mount Shasta, California. But that’s another story.

However, there was also a positive change: Books didn’t have to be shelved, necessarily, where the system told us to shelve them. This was, I feel, the last imprint I left on the horror section: being empowered to seek out potential titles in other sections, and to place them in horror.

Now, Horror is a wide umbrella of a genre. The writer Peter Straub is very close to my heart, and I often revisit talks and interviews he gave. There was a talk where he discussed having his view of the horror genre broadened greatly, which was both difficult for him to accept and, simultaneously, quite liberating, since he himself had long struggled with the label of “Horror Writer,” being such a deeply literary writer in the genre. I think of Straub as an amazing example of a writer and a person who seemed always to be evolving. The example he offered as being readable as horror was Herman Melville’s Bartleby. Someone in the audience said, “Really? Bartleby, horror?” To which Peter Straub answered, “Why not?”

In my own writing, I often worry that I’m not “horror” enough for horror. But then I think of Peter Straub saying, “Why not?” And I think of my own taste in books alternating often between quieter literary fiction and horror fiction—often meeting somewhere in the middle with my favorite works of unconventional literary horror. I think of these things and I feel reassured, invigorated, and glad.

So, oddball titles ended up in my section, titles that normally would’ve been shelved elsewhere, such as titles from Julia Armfield, Ness Brown, Jenny Hval, et al. (Though, if you go to the section now, that won’t be the case, as I believe this has already been reversed since my leaving).

On my last day at Barnes & Noble, I spent more time chatting with my coworkers than I was normally able to. I had fun with a few customers, shared a few wonderful “farewell” exchanges with some of them, even. And I spent a lot of time in my Horror section. Put in a few final shortlists, straightened everything up, restocked a few titles from the back, reread my many (possibly too many) shelftalkers which many customers over the years had thanked me for. I took photos of the shelves, smiled at both my books (and possibly stealth-signed a handful), and left the section as mine for the last time.

My growth as a reader, writer, and lover of horror had the backdrop of that horror section for a few years. Through it, I discovered so many incredible and influential writers, and a number of now cherished favorites. When I published The Family Condition and, later, The Aching Plane, the section felt like a line connecting me, even just in a small way, to the writers who inspired me, allowing me to support—from my small corner—the absolutely lovely horror community. It even helped me become part of the local horror community in a small but meaningful way, with a few friends I made through a love of horror, and the Horror Book Club I still run.

This is really just a sentimental love letter to a bookstore’s horror section and my history with it, how it helped shape me while I was shaping it. But I like to think of it as having Lovecraftian tendrils reaching out across the horror community, reaching readers and writers the way books do. It was a joy and an honor to be part of it.

Lastly, I’ve named many voices in the horror genre in this blog post. If you need a resource for authors to look out for in the genre, I’d recommend looking into their work. Their work made mine, with this horror section, a more than worthwhile experience.